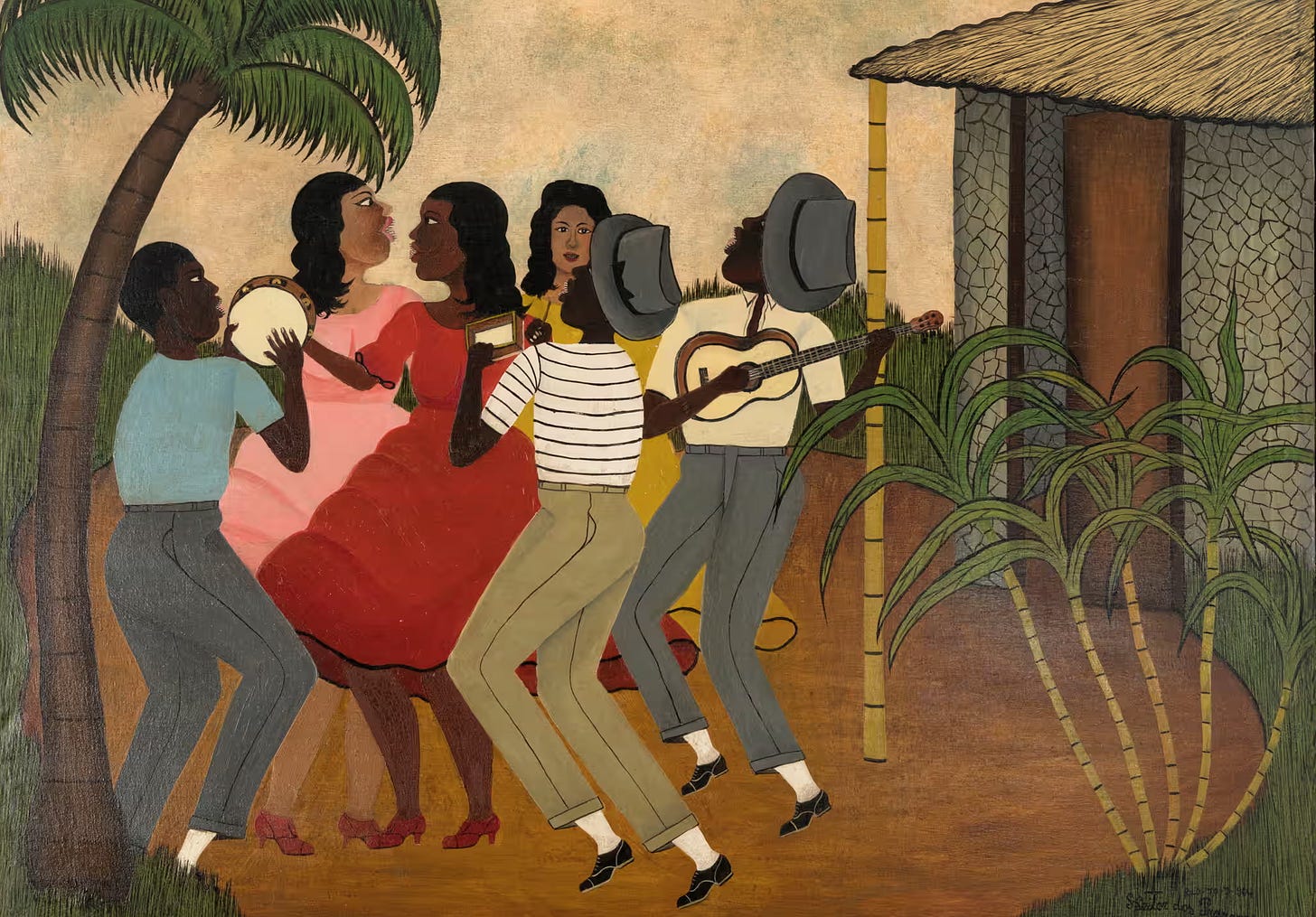

Untitled, Heitor dos Prazeres (1965)

This Must Be The Place is currently on sabbatical, so you’ll see a change in the regular scheduled programming until the end of March 2025. In the meantime, to feed the hungry content beast, I’ll publish some notes from my travels: first, Brazil.

i.

Mr B was my geography teacher. We did not see eye-to-eye.

I considered him a curmudgeonly throwback who had long lost interest in teaching; I suspect he thought me cocky, not as clever as I thought, and disruptive (all fair assessments). This antipathy was perhaps inevitable: in my family of historians, geography was habitually shunned, dismissed. In my father’s personal mythology, he so disdained the subject that he willed himself to fail his O-Level.

All that is to say that I didn’t thrive in geography class and rarely paid attention. But in my fragments of recollection from those fraught and tiresome lessons, I remember talking a lot about Brazil. Specifically: favelas in Rio, and deforestation in the Amazon. So I wonder: would Mr B feel a blush of pride to learn that the first three weeks of my sabbatical took the form of a geography field trip?

ii.

Mention Brazil and the instinctive mental images are these: white sand beaches, gravity-defying arses, dense rainforest, Carnaval, Christ the Redeemer - and crime. My wife has a colleague from southern Brazil - an area considered more refined, and aloof, than the wild north - who is horrified to learn that we are going to Rio, and checks in frequently to ensure we haven’t been murdered. Our mothers have similar fears, expressed quietly but unambiguously.

The concern is not without basis: like much of Latin America, Brazil has a serious homicide problem. Its murder rate is almost five times higher than the world average, and in 2018 it had the highest number of killings of any country. Petty crime is also endemic in the cities. Reassuringly, though, guidance for tourists makes clear that the serious crime is largely confined to the favelas. Just keep your wits about you. Stay away from the favelas, and you’ll be fine.

Yet these fabled centres of crime and deprivation have themselves become unlikely tourist destinations. On previous trips to Cape Town and Medellin, we eschewed tours of townships and comunas - it felt distinctly questionable to treat the city’s poorest areas as human zoos, photographing poverty to post on Instagram. But the Lonely Planet is so adamant that one Rio guide does it ethically that we overcome our concerns, give in to curiosity, and book a walking tour of the largest favela in South America.

Rocinha straddles a steep hillside in southern Rio, sandwiched between old money neighbourhoods and the beach. It’s home to over 200,000 people. And, while it’s a far cry from the strutting glamour of Copacabana and Ipanema, it’s also not the abject slum of our imaginations. The buildings seem permanent; there are banks, bars and (largely stolen) broadband; tottering piles of rubbish, added to by passing motorbikes, are promptly collected by local binmen.

But its problems are complex: the favela is run by a drug cartel called Comando Vermelho - and, beyond intermittent crackdowns, the Brazilian police allow this situation to continue. As long as the cartels aren’t shooting each other, they are left to their own devices. The kingpin in Rocinha is known as ‘Johny Bravo’ - a man our guide assures us is a ‘genius’, who speaks seven languages with such a level of fluency you would mistake him for a native. The tour company operates in the favela with the permission of the cartel; we wonder if our guide has gone native herself.

Weaving through the cramped and narrow streets, we come to an opening where a small group of children is playing basketball. Their coach is a retired Brazilian player, born in the favela. After a career spent in Europe and Japan, he has returned home to help the children of Rocinha thrive. He is passionate and sincere, and tells us earnestly that the favela is bursting with potential. We feel that. But we suspect the cartel is not the organisation to harness it.

iii.

Para inglês ver is a Brazilian expression which means, essentially, to keep up appearances; outwardly to adhere to the formal rules but to behave rather differently behind closed doors. It translates as: for the English to see.

The phrase originated in the transatlantic slave trade, during which Brazil imported 4 million enslaved Africans - more than any other country. In 1826, in a fit of abolitionist zeal, the British forced Brazil to sign a treaty that eliminated the slave trade - at least formally. But Brazil had no desire to suppress a practice which was then crucial for its economy: they kept up appearances internationally, para inglês ver, but clandestine importations of slaves continued until at least 1850.

200 years later, and the international pressure applied to Brazil relates instead to climate change. Brazil’s national anthem declares that the country is a “gentle mother … lying eternally in a splendid cradle.” That cradle is the Amazon - the largest rainforest in the world, the lungs of the planet - two-thirds of which is in Brazil. But (without wanting to get too Greta on you): it’s disappearing. 20 per cent has gone in a few decades, and the rate of deforestation ramped up for the first time since 2004 under the Bolsonaro government. The world is paying attention; it’s not for nothing that this week a radical Brazilian environmentalist was named Prospect's Top Thinker for 2025.

So it feels a rare privilege to visit, while we still can. We stay for five days on the banks of the Rio Negro, surrounded by dense jungle and an indescribable dawn chorus. Pink and grey river dolphins pop out of the muddy water as we watch from our porch. We spend our mornings in low-lying boats spotting iguanas and sloths in the trees, nosing into floating homes, wishing we’d brought better binoculars. We hike through virgin jungle, scare a tarantula, get savaged by mosquitoes. We vow to do more for the environment: just after we fly back from sabbatical. But for now, we continue, para inglês ver.

iv.

How can you immerse yourself in a country as a tourist? It’s a tricky one. As we experience among the throngs surrounding Christ the Redeemer, modern cultural immersion tends to consist of taking gormless selfies in front of tourist attractions. The hungry content beast will never be sated. But surely there’s a better way?

We have three weeks in Brazil, which seems a long-ish time; but when you’re faced with the world’s fifth largest country - where a bus between two apparently adjacent cities takes 17 hours - it feels hopelessly inadequate. Brazil is incomprehensibly vast, unimaginably diverse. In the circumstances, it’s helpful to have some shortcuts to cultural understanding.

When travelling, I often try to read something tangentially related to the country I’m visiting - so, Elena Ferrante when in Italy, Burmese Days in Myanmar, Gabriel Garcia Marquez in Colombia. This gives me the vague sense I am engaging with the country, rather than just enjoying the weather. The idea, I suppose, is immersion through osmosis - I’m not sure it’s meaningful, but it makes me feel a bit better about travelling somewhere with only a clumsy ability to communicate in the local language.

Continuing this practice in Brazil is not entirely straightforward. Despite its size, Brazil’s novelists have not made a significant impact on the western canon: unlike its neighbours, Brazil has no Borges, Marquez or Bolaño. So finding a great work of Brazilian literature to read on this trip is trickier than anticipated. But after some searching, I come across The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas by Joaquim Maria Machado De Assis, and Clarice Lispector’s Hour of the Star.

Published 90 years apart, the novels bookend 20th century Brazilian modernism: Machado has been described as the country’s first modernist; Lispector is its best known postmodernist. But despite the gap in their publication dates, these curious, creative little books share some striking formal similarities. Brás Cubas is narrated by a dead man writing his memoirs from beyond the grave; he is highly aware of his job telling the story of his life and constantly brings the reader into his narrative decisions. The Hour of the Star is similarly self-referential: the narrator brings to life his doomed protagonist, and complains frequently about the difficulty of telling her story. Both make for really fun reads.

Not wanting to limit myself, though, I also read Brazil by John Updike - a novel about the forbidden love between a lad from the favela and a girl from Copacabana (an archetypal plot, based on Tristan and Isolde). I have heard Updike described as a writer who has nothing to say, but says it beautifully - but on the strength of this offering, I wouldn’t even give him that. It’s a strange pornographic melodrama, which clumsily tries magical realism without the deftness or subtlety of Marquez. I make a note to stick to local authors next time.

v.

The phrase “time flies when you’re having fun” has always struck me as horribly inaccurate. Going through the motions, stuck in the routines of work and home life, is when time really feels it’s slipping through my fingers - when I am struck by Heidegger’s idea of finitude. When having fun, experiencing new and interesting things, however, each moment feels more significant, more worthwhile.

It is often - harshly - said that Brazil is the country of the future and always will be. Our three weeks there come to an end far too soon - but 21 days of beaches, rainforests, wild cities, grand colonial architecture, and daily caipirinhas feel like a wonderful lifetime.

Another great read. Looking forward to reading about the next leg of your travels!

Genuinely fascinating and typically truthful. I learned a great deal. Unlike, perhaps, being in Mr B's lessons. You should be a Geography teacher, David!